Why Lean Startup Is Hard In Practice

Over the last couple of years, I’ve blogged about my lean startup experiments (a popular post that made page one of HN). I’ve spoken at conferences about applying lean to building mobile apps. And, I was a mentor at Lean Startup Machine. Along the way, I’ve applied lean at my last startup across ideas incubated using an internal Y-Combinator incubation format. I’ve collaborated with other entrepreneurs as a part of a DHC lean peer group (who reviewed this post). And right now, I’m running lean experiments at Intuit, a large software company. I’ve come to the conclusion that while lean startup has been a terrific step forward in how we think about what to build next, there’s still many significant challenges involved in practice. This post is an attempt to surface some of the issues so that we can talk about them as a community, and we can learn from each other.

Before you read on, you may want to get past some of the common misconceptions about Lean Startup.

Experiment design is hard for beginners.

This may seem obvious, but it’s worth mentioning. Some folks get into lean startup thinking of it in the context of cost, but that’s a misnomer. While lean manufacturing is about cost, and is the origin of Eric Ries’ idea, Lean Startup is about translating a vision into a falsifiable business model hypothesis.

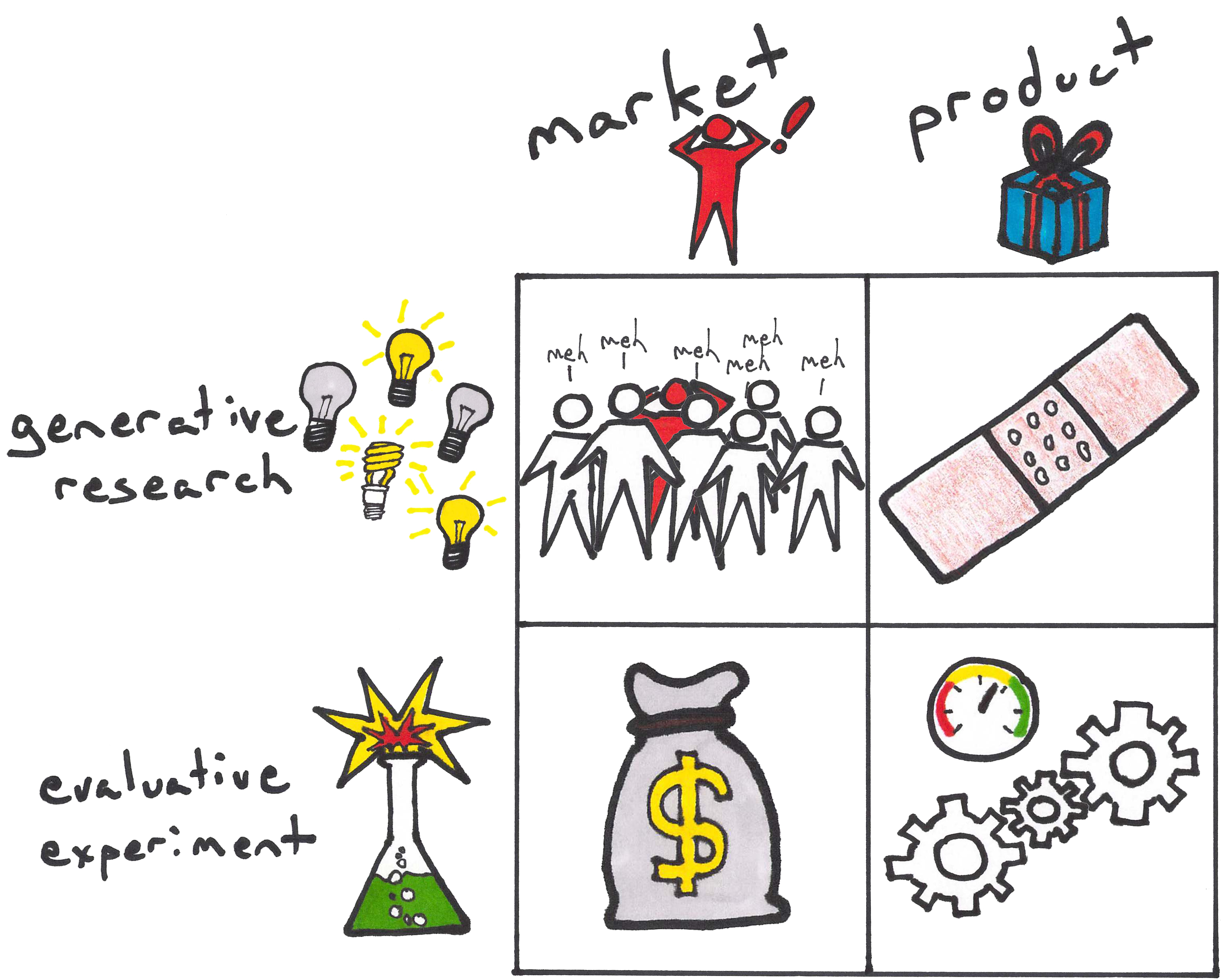

Crafting a hypothesis and finding your leap of faith needs discipline. Choices about validation criteria can be subjective and need judgment calls. Decisions about how minimal your MVP needs to be can be challenging with marketplace or mobile apps where experience matters. Is the right experiment broad based generative research or evaluative to find fitment? Are we testing for the market needs or product fitment? That said, there’s certainly a wealth of information out there now, and vibrant supportive community that’s making this easier.

There are many tools that have emerged in the last few years like Lean Canvas, Javelin Board, Lean Monitor, Lean Lab, Lean Launch Lab, Brainstormand Lean Stack. There’s even a clever board game by Simen Fure Jørgensen. There’s also several consultants and trainers offering training to help new entreprenurs or intrapreneurs apply lean startup to new ideas. While these have eased the learning curve somewhat, it’s still hard for a beginner going beyond a launch page and into his first pivot to figure out what next.

Sampling sizes need to be large enough to hold significance.

In theory, you’d want to go out and find your ideal customer whose pain your can solve well, and then find more like them. In practice, the narrative isn’t quite as linear.

When you are looking for a strong signal, but looking to test with a minimal experience, you often look for early adopters whose pain is deep enough that they would use your MVP regardless of polish. Often, it can be a challenge finding enough early adopters who match your persona to test things at scale. What then happens is, conversions rates can tend to be lower if the sampling set includes mainstream users used to refined apps with a well designed experience. One way to address this is to craft an experiment that tests if improved design bumps up conversion numbers, but this poses a judgment call about whether you have sufficient validation to invest in further refinement.

One can argue that this is all about distribution. While distribution is always a challenge for startups working through different channels for traction, these challenges exist in larger companies too. Larger organizations can be defensive about exposing key influential users (who are often early adopters) to scrappy experiments, making acquisition just as challenging.

So what ends up happening? Some run experiments with broad, large sampling sizes whose personas type may be a mismatch, leading to invalidation. Or, run with smaller groups with qualitative feedback that yields deeper insights, but may not be statistically significant.

Whether choosing criteria for validation or making a pivot vs persevere decision, we’re often faced with situations that require a judgment call. Despite our best intentions, our decisions are often swayed by our biases. While our understanding of cognitive psychology may have improved over the year, we often let our biases get the better of us.

Sometimes we often spend endless analyzing things, and make ourselves believe we are arriving at deeper insights by armchair analysis. Instead, we are often just rationalizing our own thoughts with dialectical skills. While Lean Startup provides a framework that appears to helps reduce otherwise rampant confirmation bias, it doesn’t necessarily provide all the answers.

Managing control variables across experiment batches requires rigor and persistence.

A common challenge I’ve seen has been identifying the control variables that influence your experiments and managing them across experiment batches. Without this in place, it can be hard to draw a strong correlation, and understand if you were invalidated or not.

For instance, it’s easy to mix up testing out a channel hypothesis with a value hypothesis and get muddled. One of the medical startups that was at Lean Startup Machine went out and spoke to ten people on the street to test their initial value hypothesis. They got a lukewarm signal, but decided to persevere with a modified value hypothesis. They then went out and spoke to ten people at hospitals. Since the signal was weak, they felt they were invalidated, but weren’t sure if their original value prop might have appealed to the hospital.

In scientific lab experiments, control variables are carefully managed. If an experiment is run again with the same setup, the same results are expected. If not, the original experiment is usually considered to have been flawed.

However, tests in the real world are exposed to several variables which are often beyond our control. While a scrappy approach helps us try things out quickly, keeping in mind the different control variables that apply to your experiment and holding them constant may help derive better inferences about the result of an experiment.

Risk of missing big opportunities.

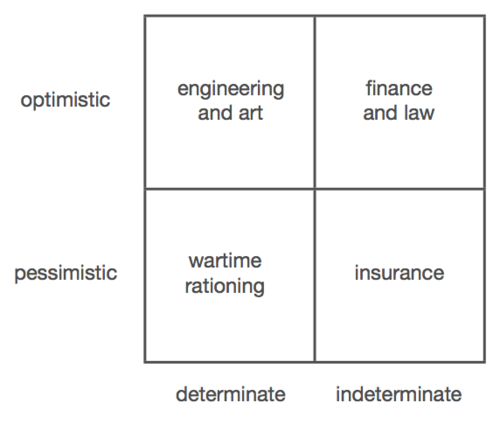

I think it was Peter Thiel who opined that we may have swung too far from ‘determinate optimism’ towards ‘indeterminate optimism’. He appears to believe that the Lean Startup approach of attempting small bets make not really translate into big high impact ideas that can disrupt industries.

Indefinite futures are inherently iterative. You can’t plan them out; things just unfold on top of each other. The question is thus whether an iterative process can lead, if not to the best of all possible worlds, at least to a world where there is a path of monotonic and potentially never-ending improvement. If it can, we may not get to the tallest mountain in the universe. But at least we’ll always go uphill.

Put simply, he doesn’t think you can experiment your way towards a grand vision. But on the other hand, many great startup ideas that seem visionary now sounded terrible when they started.

Iteration and machine learning are often excuses for not thinking about the future and short time horizons.

Part of his thought process there is that post the 2008 subprime crisis, the world has largely slipped away from the top left quadrant towads the bottom half.

Effectuation and Lean Startup

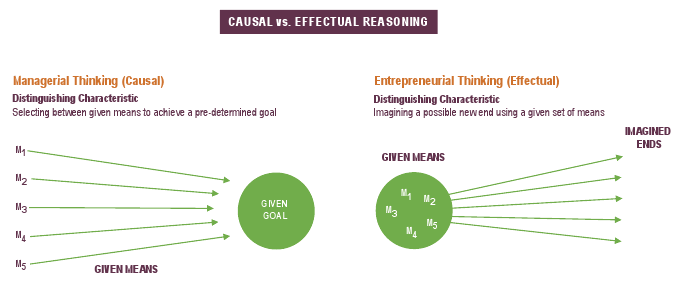

There’s also the views of Professor Saras Sarasvathy, who was a speaker at a fabulous iSprt roundtable last year. Saras’s paper on “What makes entrepreneurs entrepreneurial” is now regarded as a seminal piece on Effectuation.

In simple terms, her view is that causal reasoning is used when the future is predictable. But effectual reasoning is used when the future is unpredictable, which is most often the case for entrepreneurs. She believes that instead of causal or systems thinking, entrepreneurs look to leverage available resources at hand to see where they can go from there. In many ways, some of her ideas resonated with the audience and felt more intuitive than Lean Startup. Some, like Rob Fitzpatrick have opined that Effectuation may be the better suited tool to decide what to do next.

Ultimately, most of these views are inherently hard to digest since there’s no easy way to examine how any of these approaches are working in practice. While there are some people who claim to have succeeded using one framework or the other, those declarations have mostly come after they achieved success with limited visibility into the journey. Are we just falling for survivorship bias?

Slope of Enlightenment?

10/Founders and employees often have running room to try multiple products within a single startup; hence popularity of the term "pivot".

— Marc Andreessen (@pmarca) March 24, 2015That @pmarca storm emphasizes two key ideas: founders can gain portfolio economics via 1. pivots and 2. making entrepreneurship a career

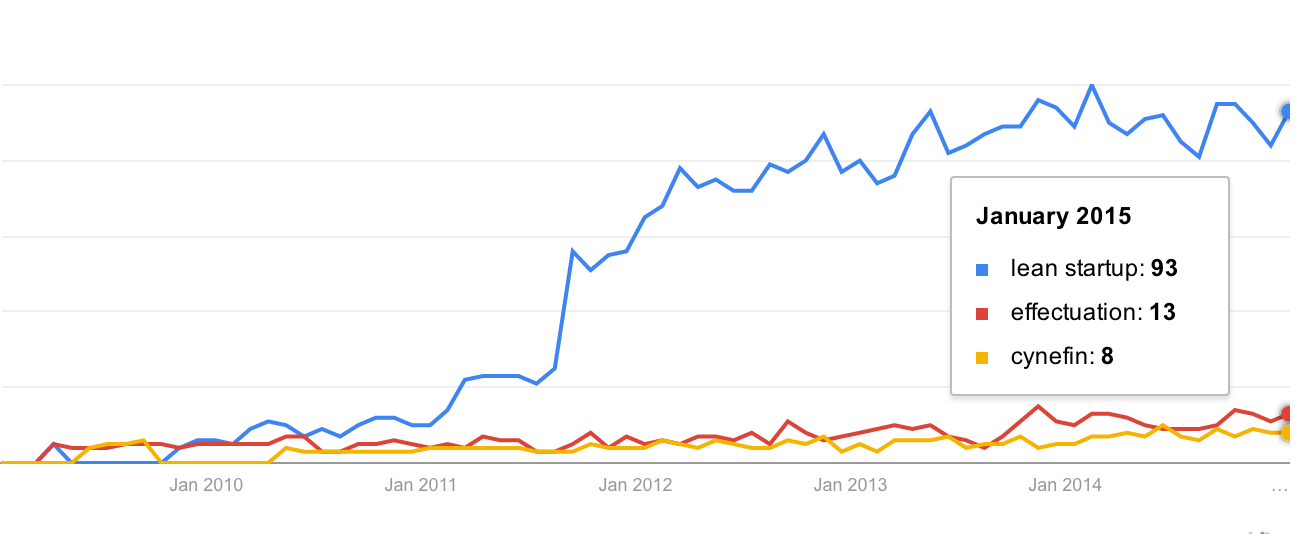

— Eric Ries (@ericries) March 24, 2015It feels like we are past the peak of inflated expectations around lean startup. But are we on to the slope of enlightenment quite yet?

Irrespective of whether we are in a startup or a big company, we’ve come a long way in the last decade with how we think about building products. Lean Startup has radically changed how we think about taking a new idea forward. While there are challenges, it’s great that there is an active community that shares ongoing experiments and trades notes. Continuing to do this will help us learn from each other, and continue to refine our working models.

We are now well beyond thinking of lean startup solely in terms of cost saving, or an excuse to put out half assed MVPs, or to keep pivoting at a whim. If you believe the traction Eric seems to have around his new book The Leader’s Guide, a significant community has embraced Lean Startup in the context of both entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship across a wide range of industries. While challenges remain, we continue to learn.

We cannot afford to have our success breed a new pseudoscience around pivots, MVPs, and the like. This was the fate of scientific management, and in the end, I believe, that set back its cause by decades.

If you have suggestions or examples from your experiences, please drop me a note or connect via Twitter @twitortat.