What We Learnt From A Failed MVP (Lean Startup)

UPDATE

Read the follow on post on lean startup customer development interview questions, that’s part of an ongoing series on this blog.

Rovio tried 51 games before hitting upon Angry Birds. We tend to hear a lot more about the chart busting numbers of Angry Birds than the struggles of the previous 51 games. In my opinion, their success was the journey of the 52 experiments, and not just the final one.

We at Levitum recently had learnings from an MVP that we put out, and experiments that we ran. In the spirit of openly sharing how I’ve tried to apply Lean Startup principles to a new venture, I’m going to outline how we went about things, and what I’ve learnt.

Initial Vision

Here’s the initial vision, target audience, and problem statement that we started off with.

| VISION | A fun place where people make new friends online. |

| TARGET | Teens, College kids, Yuppies, Casual gamers. |

| PROBLEM | Connecting people online through dumb charades. |

As we thought about this, there were a number of questions.

- Do people care at all about Charades? It turned out that Ellen’s charades game was wildly popular, and there was a lot of buzz around Heads Up Charades, but that was not indicative about whether people would want to play online.

- Would charades be engaging enough that people would want to play regularly?

- If we set up a real-time game to mimic the mechanics of the game we are used to, that would require friends being present at the same time, which may be hard to schedule.

- If scheduling was hard, would people be comfortable playing with strangers in games rooms like poker online.

- Wouldn’t people freak out just a bit about turning video online? Are there communities that are more open to video online?

- If we built an async game with mobile apps so that people could play when they had time, that might work. But would it be practical for people to respond to a challenge by acting holding their smartphones in front of them?

- And then, there was the question of whether we had an interest and competencies in gaming.

The Big IFs

We set out to break these down and tackle what we felt were the biggest ifs on our list.

- If people are interested in playing charades online, and

- if they are comfortable turning on video, and

- if they like the concept enough to invite friends or join a public game room, and

- if they enjoy the playing experience with others in the room, and

- if they enjoy this enough to keep coming back, and

- if they will invite other people, we had a shot at something.

Next, we attempted to structure experiments around the major leap of faith assumptions being made, in order to seek validation.

Hypothesis 1

Of a sampling set of people searching for Charades online, at least 25% will sign up to check out the game.

| AUDIENCE | People looking to play charades online. |

| ACQUISITION | Google Ads. |

| VALIDATION | % of signups. |

| EXECUTION | 1. Build signup page in a day. |

| 2. Identify keywords, run ads for a week | |

| 3. Track signups | |

| RESULT | We ran ads targeting users who searched for ‘charades online’, ‘charades games’, and ‘charades words’. Over 25% of the users signed up. |

| LEARNING | There’s a interest in playing charades online amongst those who google for it. |

Hypothesis 2

Of users in the target demographic who are shown mocked up up flows of the game concept, at least 70% of them would be very interested in the game.

| AUDIENCE | Young Adults in India |

| ACQUISITION | Friends Network |

| VALIDATION | % of people who are very interested in the game. |

| EXECUTION | 1. Build rough mockups using MockFlow in a day. |

| 2. Walk people through the mockups | |

| 3. Collect feedback. | |

| RESULT | Overall, there unanimous interest in the game concept. A few mentioned that they may be uncomfortable being on video online. |

| LEARNING | In general, charades is popular in India, and people are interested in trying out an online game. |

Hypothesis 3

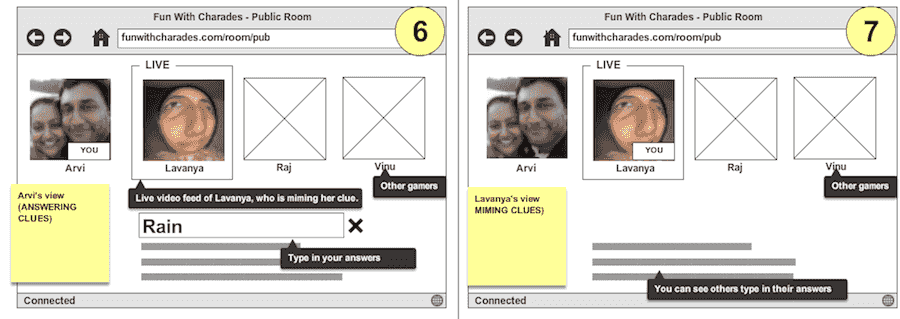

Of signed up Charades users invited to a game room, at least 25% will be willing to join a public room and turn video on.

| AUDIENCE | Signed up users |

| ACQUISITION | N/A |

| VALIDATION | % of users who turn on video in a public room. |

| EXECUTION | 1. Invite users to the public room |

| 2. Provide an explanation about what the game is about. | |

| 3. Enable the user to turn video on and start the game. | |

| 4. Track analytics. | |

| RESULT | 80% of the users visited the page, but < 5% turned video on. |

| LEARNING | This experiment invalidated our false hope that people in this era of Facetime and Hangouts wouldn’t hesitate to turn video on. We needed to dig deeper, and talk to users to understand what they felt. |

Hypothesis 4

Users are more likely to be comfortable turning on video if they are playing with their friends, and 80% or more will turn video on.

| AUDIENCE | Friends of Friends who are acquainted with each other, but don’t know each other well. |

| ACQUISITION | Friends Network |

| VALIDATION | % of users who turn on video on. |

| % of users who like the game idea enough that they would be disappointed to not play. | |

| EXECUTION | 1. Invite users to the public room |

| 2. Provide an explanation about what the game is about. | |

| 3. Enable the user to turn video on and start the game. | |

| 4. Track analytics. | |

| RESULT | 100% of the users turned video on, and were excited and ready to engage in the game. They felt they would be very disappointed if they were unable to play. |

| LEARNING | Women in the group, when asked if they would play with people they didn’t know online, said they would hesitate. Men in the group unanimously said they would be willing to try. |

Hypothesis 5

Users from online communities that use video a lot with strangers are likely to be comfortable playing with each other, and at least 25% will turn video on.

| AUDIENCE | Chatroulette and Chatrandom communities. |

| ACQUISITION | Google Ads |

| VALIDATION | % of users who turn on video on. |

| EXECUTION | 1. Run Google Ads for ‘chatroulette’ and ‘chatrandom’, offering video based charades online, and an opportunity to meet new people. |

| 2. Invite users to the public room | |

| 3. Provide an explanation about what the game is about. | |

| 4. Enable the user to turn video on and start the game. | |

| 5. Track analytics. | |

| 6. Added a Qualroo style prompt to find out why they don’t turn video on. | |

| RESULT | 50% of the users visited the page, but < 10% turned video on. 5% answered the prompt indicating they didn’t want to turn video on, would try later, or weren’t sure how to turn it on. |

| LEARNING | Given the anonymity of these communities, it was hard to reach out directly and get feedback. The sampling size of the responders to the prompt was too small to infer enough. |

The Conundrum

We also spoke to a group of users and collated feedback. So, at this point, we were faced with this conundrum from our learnings.

- There’s a certain level of interest in charades, but it’s mostly seen as a family & friends game.

- For those who see their friends & family often enough, playing charades online wasn’t appealing. (Playing live with them during Thanksgiving or Christmas was still appealing).

- The average users isn’t comfortable playing with random strangers online.

- Even communities that are comfortable dealing with nudity online, and have no reservations didn’t find the idea appealing.

- Improvements in the visual design and explanatory information offered did not increase conversions.

- A game like this requires a fairly engaged community, and it didn’t appear that charades would sustain that level of engagement.

- There’s a community of people in the subcontinent that loves dumb charades, but the version that’s played is fairly technical and geeky, and would not scale out.

What we did well

- Capture our thought process and assumptions, laying out things that had to be true for us to succeed

- Identified small batches that could be proven (or disproven) with minimum cost, rapidly built and iterated through the batches.

- Stayed honest and objective, tracked metrics and cohorts well.

What we could have done better

- Most early feedback was from subcontinent users, since reaching out the an international audience was not easy. However, these were not fully representative of the target audience.

- We built more than we should have before we understood the gaps in our understanding of the customer and their behavior.

- Included more inline surveys early on enough to have better insights.

Was this a ‘failed’ MVP?

An MVP is an experiment or a tool to help answer a high risk question. From that perspective, we would have have failed if we had learnt nothing from our experiments. I’d like to think that we succeeded in learning a lot, and that made this MVP successful.

However, one thing I noticed after I moved back to India from the Valley was that we often hesitate to talk about failures, and what we learnt from them. People are much more interested in learning from a success story. However, if you ask me, I’m more interested in the 51 attempts of Rovio than just the one that made it big. It’s the failure to learn that’s a failure.

The Decision

While we still believe in the original vision, and it’s possible that persevering and keep this going out there in the wild may yield something, we’ve decided to put this on hold. Although this is neither a hardcore game or a heavy social game, it requires gaming chops that we don’t have. Our competencies lie in mobile + social and we’re sticking to those. However, the learnings have been useful, and have helped up develop more structure around how we approach customer development, gain early feedback, and rapidly iterate to test out key assumptions. It’s more important that we develop a method that will help us get predictable around how we solve customer problems than getting lucky. I’m sure these will help us as we move on to the next stepping stones.

FEEDBACK

Are there things that you think we could have done differently? Chime in via the comments. This article made it to the first page on Hacker News.

UPDATE

Also, you may want to read the follow on post on lean startup customer development interview questions.